The investigation of burial practices among early human species unveils fascinating insights into their cultural behaviors and belief systems. Recent findings in the Levant region suggest that both Homo sapiens and Neanderthals began to engage in burial rituals approximately 120,000 years ago. This revelation raises questions about the social dynamics between these closely related groups. The implications of shared burial traditions and the nuances of their differences contribute significantly to our understanding of human evolution and social practices during the Middle Paleolithic era.

The Birthplace of Burial: Cultures Collide

Research conducted by teams from Tel Aviv University and the University of Haifa on burial sites has unearthed evidence that suggests western Asia was a pioneering ground for the practice of interring the dead. The discovery of 17 Neanderthal burial sites alongside 15 sites attributed to Homo sapiens indicates that these hominins not only shared a geographic space but also cultural practices to a certain extent. The timing and location of these burials challenge conventional beliefs regarding the chronology of burial practice, particularly when considering that older burial sites are found in this region compared to those later established in Europe or Africa.

The researchers postulate that the emergence of these burial practices correlates with intensified competition for resources and territory, consequent to the cohabitation of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. As these two groups navigated their existence in overlapping spaces, the necessity for cultural expressions—like burials—may have developed as a shared response to environmental and social pressures.

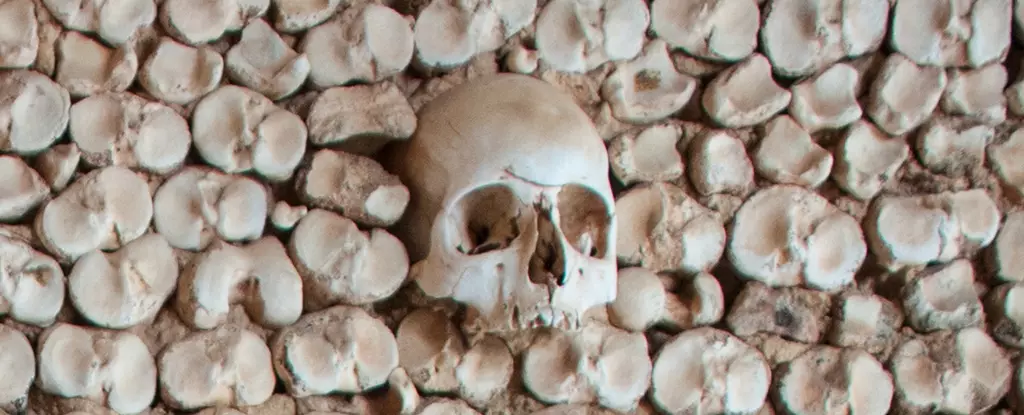

Differentiating between intentional burial practices and natural deposition—where deceased bodies are left vulnerable to the elements—poses challenges for archaeologists. The research team focused on key factors: the position of the skeletons, the presence of grave goods, and signs of deliberate burial activity. Intriguingly, both groups demonstrated a willingness to bury individuals across all age demographics, though the frequency of infant burials appeared to be more pronounced among Neanderthals.

Grave goods provided an interesting contrast; both cultures included offerings such as stones and animal remains, but their arrangements and significances varied. Among Neanderthals, burials typically occurred deeper within cave structures, often yielding diverse orientations of the skeletons. In contrast, Homo sapiens utilized more accessible locations like cave entrances and rock shelters, often positioning their deceased in a fetal-like manner, which may reflect a different set of beliefs about life, death, and the afterlife.

The contrasting burial practices reveal differing cultural narratives. Neanderthals incorporated natural elements—such as rocks—potentially serving as primitive gravestones. In comparison, Homo sapiens adorned their graves with decorative materials, including ochre and shells, reflecting a more complex level of ritualistic significance. The absence of similar ornamental practices within Neanderthal burials may indicate a divergence in their spiritual or symbolic comprehension of death. The evidence suggests that although these groups shared certain cultural traits, their expressions of mourning were distinct in character.

This duality of shared practices interlaced with unique elements ultimately complicates our interpretation of Neanderthal and Homo sapiens interactions. As both groups engaged in burial rituals, the possibility of not only collaborating but competing for cultural dominance emerges.

The extinction of Neanderthals around 50,000 years ago presents an intriguing gap in the archaeological record. Following this decline, there was a notable pause in human burial practices within the Levant for tens of thousands of years, prompting further inquiry into the potential socio-cultural impacts of such an extinction. It raises questions about how the absence of Neanderthals influenced the behavioral adaptations of H. sapiens.

New burial trends resurfaced toward the end of the Paleolithic epoch, coinciding with the advent of sedentary societies and the transition to complex hunter-gatherer communities, such as the Natufians. The re-emergence of burial practices in this later era introduces significant avenues for understanding the transformation of cultural expressions related to death and commemoration.

The collaborative yet competitive relationship between Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens is essential for unlocking the complexities of human prehistory. As research continues to elucidate the subtleties of their burial practices, we glean vital knowledge about not only the interactions between these species but the evolution of human cultural development as a whole. By piecing together the fragmented narrative of ancient burial customs, we steadily construct a more nuanced understanding of our ancestors and the social fabric that shaped early human life.

Leave a Reply