Recent studies have attempted to explore the complex relationship between antibiotic use and the risk of developing dementia among older adults. While some studies previously suggested a potential link, a prospective study involving over 13,500 participants aged 70 and older found no significant association between antibiotic use and dementia risk over a follow-up period of approximately 4.7 years. This article delves into the methodologies of these studies, the implications of their findings, and the nuances in interpreting their results.

Conducted by a team led by Dr. Andrew Chan from Harvard Medical School, the study sought to clarify the earlier murky relationship between antibiotics and cognitive decline. Participants, who were part of the ASPREE (Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly) trial, did not exhibit a higher risk of dementia or cognitive impairment associated with antibiotic use. The statistics spoke for themselves: the hazard ratio for dementia incidence stood at 1.03 with a confidence interval of 0.84-1.25, indicating no meaningful increase in risk for those using antibiotics compared to non-users. Similarly, the likelihood of developing cognitive impairment with no dementia remained unchanged, as shown by a hazard ratio of 1.02.

This extensive analysis indicates that, at least for this specific cohort of healthy older adults, antibiotics may not impose a significant risk in terms of cognitive health. The researchers noted that during the observation period, 461 cases of dementia and 2,576 instances of cognitive impairment were recorded, yet no corresponding evidence linked this to antibiotic exposure.

An important aspect of this study is the profile of its participants. Recruited from Australia and the United States, all participants were free from major health conditions such as serious disabilities, dementia, or acute illnesses at the start of the study. This selection resulted in a relatively homogenous group, with an overwhelming majority being white and aged around 75. Such a narrow demographic limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader older population that may present varying health profiles and risks, including co-morbid conditions commonly associated with cognitive decline.

Wenjie Cai and Alden Gross from Johns Hopkins University echoed this caution in their editorial, emphasizing the need for clinicians to be prudent when applying these findings to diverse patient populations. They highlighted that while the study contributed valuable insights, it should not serve as the definitive guide for antibiotic prescribing practices among all older adults.

The prevailing skepticism surrounding antibiotics and cognitive decline is bolstered by previous research that portrayed a more cautionary tale. Early studies like the Nurses’ Health Study II indicated detrimental effects on cognitive scores in women who were prescribed antibiotics during midlife. Additionally, earlier small-scale trials had hinted that antibiotic treatment could affect cognitive decline differently in Alzheimer’s patients, further muddling the waters of understanding antibiotic implications.

These conflicting strands of evidence point to the critical need for a more nuanced exploration of this topic. It raises questions about the types of antibiotics, duration of use, and individual patient factors that could likely influence outcomes. The present study hints at a lack of direct causation but fails to fully address the complexities of how different antibiotics might interact with cognitive health differently based on patient profiles.

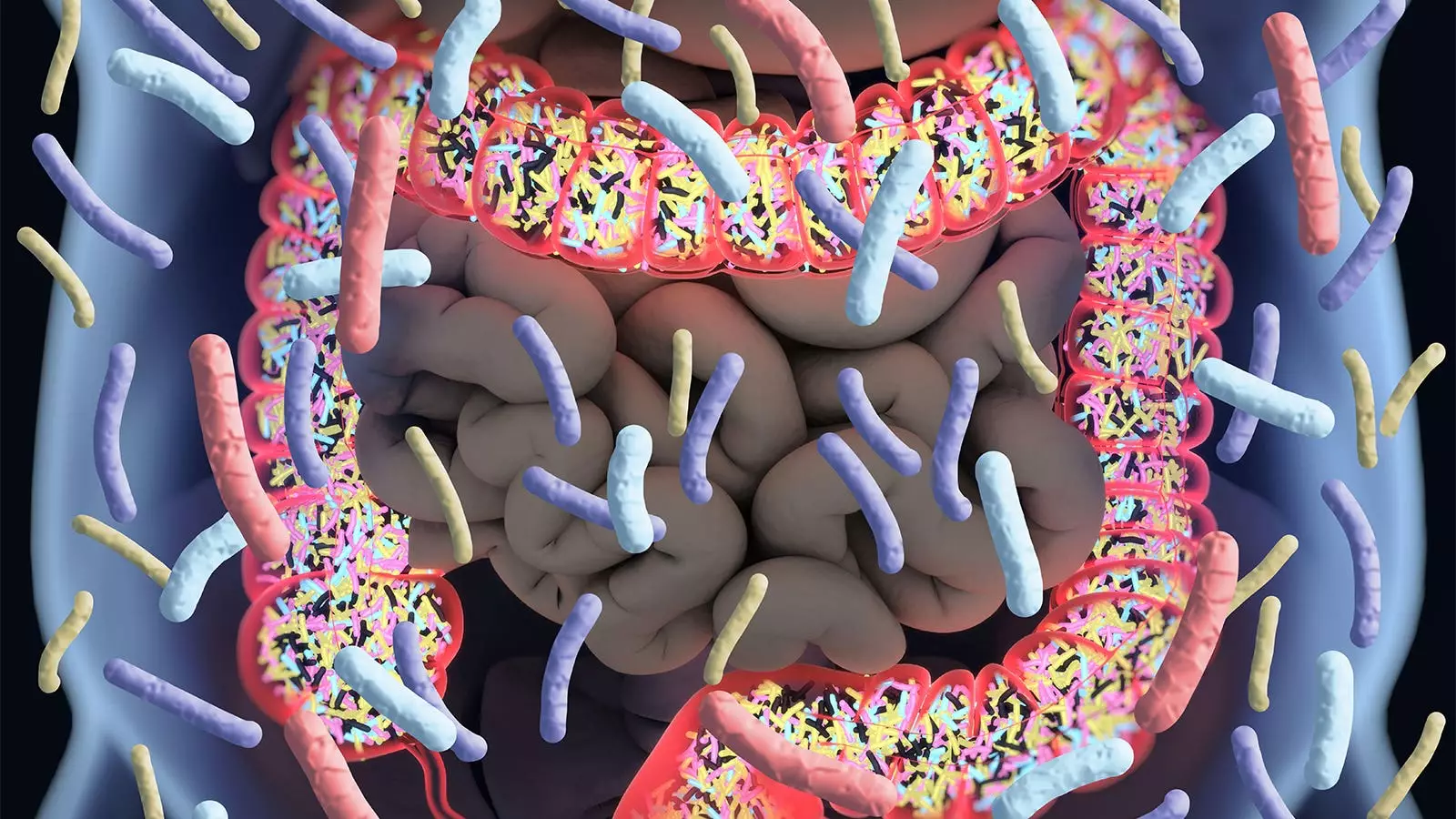

Dr. Chan noted the pivotal role of the gut microbiome in overall health, including potential links to cognitive function. Given antibiotics’ well-documented ability to disrupt this microbiome, concerns linger about their long-term impact on the brain. The researchers themselves acknowledged this critical interplay between gut health and cognitive functions but were unable to draw a definitive correlation with their findings. This uncertainty paves the way for future research to explore this interaction more comprehensively.

The recent findings from the ASPREE trial offer a degree of reassurance about the safety of prescribed antibiotics concerning dementia in healthy older adults. Nonetheless, the study has limitations, particularly in its applicability to a more general elderly population. As antibiotic therapy remains a common practice in geriatric medicine, further interdisciplinary research is essential to effectively balance the necessity of antibiotic treatments with the broader implications for cognitive health. Continued exploration into the nuances of how various factors influence both antibiotic efficacy and cognitive outcomes will be crucial for future clinical guidance and recommendations.

Leave a Reply