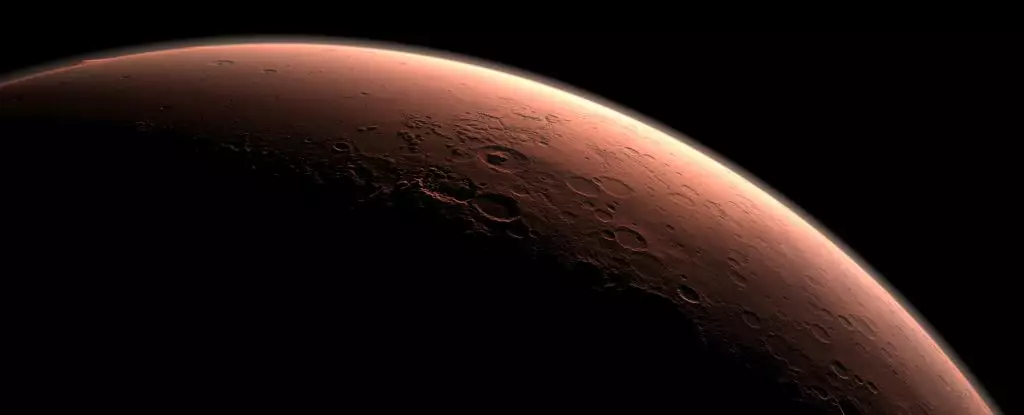

Despite decades of exploration, the quest for extraterrestrial life on Mars remains unfulfilled. Although scientists have meticulously searched the rust-colored planet, they have yet to uncover definitive evidence supporting the existence of life. The Viking landers, which touched down on Mars in the 1970s, were the first US missions to conduct in-depth studies of Martian soil. These ambitious exploration efforts have raised tantalizing possibilities, suggesting that life might have existed under certain conditions. However, a closer examination of the methodologies employed during these initial missions raises significant concerns about whether we inadvertently eliminated the very signs of life we aimed to uncover.

Astrobiologist Dirk Schulze-Makuch from the Technical University of Berlin has expressed critical insights regarding the Viking missions, particularly focusing on the experiments designed to detect microbial life. According to Schulze-Makuch, the very processes engineered to uncover signs of life may have inadvertently destroyed potential evidence. This unsettling idea compels us to reevaluate our approaches to astrobiology and the assumptions entrenched in our search for Martian life.

The Viking landers embarked on their mission with a clear agenda: to analyze Martian soil for biosignatures, hoping to detect traces of organic molecules indicative of living organisms. One notable experiment used a gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer (GCMS) that detected chlorinated organics, which were initially brushed off as contamination from Earth. In retrospect, this finding may compel us to reconsider our assumptions; as we learn more about Mars, it’s becoming evident that we must explore the possibility that these compounds are indigenous to the planet.

One of the foremost issues with the Viking experiments is their reliance on conditions modeled after Earth. Each trial assumed that Martian life forms, if they existed, would resemble terrestrial organisms and thrive in moist environments. However, recent discoveries indicate that life can adapt to arid conditions. Consequently, imposing a wet environment on Martian samples may produce misleading results by overwhelming organisms that have evolved to survive with minimal liquid.

Schulze-Makuch highlights a relevant analogy: envision an alien spacecraft locating a stranded human in a desert and deciding to “rescue” the individual by placing them in an ocean. This method of treatment would not yield a successful rescue; similarly, pouring water on dry-adapted Martian organisms might lead to their destruction. Interestingly, preliminary results from the pyrolytic release experiment demonstrated stronger life signatures when water was absent, raising further questions about the validity of our tests.

The inconsistencies in the Viking experiments paint a perplexing picture. Although some results hinted at possible life, they were frequently dismissed or overshadowed by negative results in other tests. Specifically, the seemingly contradictory outcomes of the labeled release and pyrolytic release experiments—where one indicated potential biological activity while another showed none—continue to baffle researchers. This discordance suggests that potentially significant evidence might have been disregarded, warranting a nuanced reevaluation of historical findings.

Furthermore, Schulze-Makuch’s pioneering concept from 2007 proposes that Mars could harbor life forms uniquely adapted to extreme desiccation, even using hydrogen peroxide as a component of their biological machinery. This hypothesis does not conflict with the Viking results but instead invites us to think along unconventional lines. Such perspectives may not only broaden our understanding of life beyond Earth but also refine our methodologies in the ongoing Martian exploration.

The implications of Schulze-Makuch’s critiques have the potential to influence future missions to the red planet. To avoid repeating the mistakes of the Viking missions, future endeavors should be centered around experiments designed with the unique Martian environment in mind. Dedicated missions focused on the search for extraterrestrial life must embrace diverse methodologies that regard both dry-adapted life and the potential for indigenous compounds as viable focal points.

As we stand at the forefront of new explorations, it is imperative to heed past lessons. The Viking missions may have brought us closer to understanding Mars’s potential for life but also revealed significant shortcomings in our methods. By adopting refined approaches and broadening our inquiries, future missions may yet uncover the elusive signs of life on our neighboring planet. The search for Martian life is not merely an exploration of an alien landscape; it represents a journey into understanding life’s resilience—a quest that continues to beckon humanity in the enduring expanse of the cosmos.

Leave a Reply