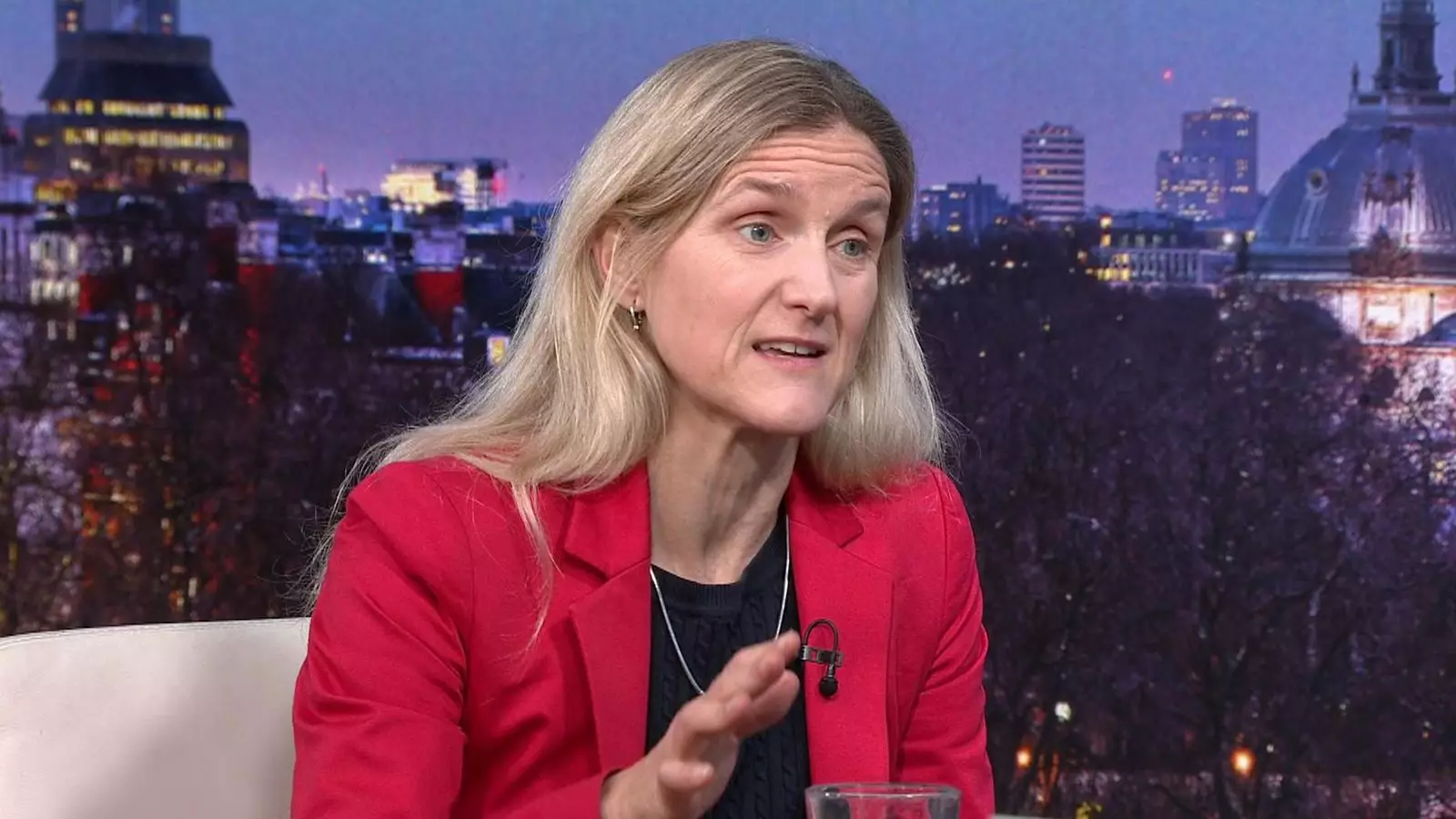

In a contentious landscape marked by diverse personal beliefs and ethical considerations, the discussion surrounding assisted dying in the UK is gaining momentum. Labour MP Kim Leadbeater is at the forefront of this debate with her proposed amendments to the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill. As discussions heat up, the implications of these changes warrant closer examination.

A Shift in Oversight Structure

One of the most significant proposals from Leadbeater is the removal of the necessity for a High Court judge to sign off on each case of assisted dying. Instead, she suggests the establishment of multi-disciplinary panels made up of experts who would evaluate cases for approval. This shift aims to diversify the oversight structure, allowing not just legal but also medical and psychological perspectives to come into play. The panels would consist of three members, and while a retired High Court judge or a King’s Counsel would chair these panels, the broader composition raises questions about the adequacy of legal scrutiny in such profound decisions.

Leadbeater describes this modified system as a “judge plus” framework, intending to fortify safeguards against coercion or undue pressure during the decision-making process. The argument rests on the premise that having a variety of professionals—such as doctors, psychiatrists, and social workers—will enrich the evaluation, ultimately safeguarding vulnerable individuals. Yet, there are concerns that this approach could dilute crucial legal oversight while expanding the scope of who has authority over life-ending decisions.

Opposition voices express alarm at the potential weakening of existing safeguards. Tory minister Danny Kruger labeled the amended proposal “a disgrace,” indicative of a broader concern among opponents that the bill’s modifications prioritize expedience over patient safety. Labour MP Diane Abbott and former Lib Dem leader Tim Farron have also weighed in, branding the legislation “rushed” and poorly conceived. Their criticisms underscore a significant debate within Parliament regarding whether the proposed changes adequately protect individuals who might be in fragile mental states when considering assisted dying.

The dissent not only stems from ethical considerations but also highlights a fear of unintentional consequences—especially regarding vulnerable populations like those with disabilities. Mencap, a learning disability charity, has raised alarms that discussions about assisted dying could lead individuals toward choices they would not otherwise consider, putting societal pressures into sharp relief.

The Role of Expert Consultation

In a recent interview, Leadbeater defended her proposal, asserting that the input of various professionals enhances the legislation. While she acknowledges the importance of legal oversight, her belief that a multi-disciplinary approach could better serve the complexities of end-of-life decisions is intriguing yet contentious. The crux of her argument is about achieving a balance between legal frameworks and compassionate care. By integrating perspectives from different areas of expertise, she posits that the result could mitigate risks associated with coercion.

However, this argument raises significant questions regarding the adequacy of the proposed safeguards. The reliance on expert panels requires confidence in their ability to objectively assess the emotional and psychological dimensions of each case—a task that is fraught with its own set of challenges. Any system relying on human judgment can be susceptible to bias, and the variability in expert opinion could potentially lead to inconsistent outcomes.

The amended bill is slated for committee review, where MPs will examine its particulars line by line. The committee, composed of members favoring assisted dying following a previous vote, stands to play a crucial role in shaping its future. It will be paramount for lawmakers to weigh the ethical implications and societal responsibilities tied to facilitating assisted dying against the emotional and physical suffering of terminally ill individuals seeking liberation through this measure.

As the conversation unfolds, the integration of a Voluntary Assisted Dying Commission to oversee applications intends to instill further legal rigor into the process. This commission could potentially introduce checks and balances that mitigate some opponents’ concerns, yet the fundamental debate over the ethics of assisted dying remains deeply rooted in individual beliefs and values.

The proposed changes to the assisted dying bill not only invite legal and ethical scrutiny but also challenge society to confront its values surrounding life, death, and the human experience. As MPs prepare to deliberate, the necessity for an open dialogue underscoring the importance of safeguarding vulnerable populations is more crucial than ever. The decisions made in this arena will continue to shape the broader narrative of assisted dying in the UK for years to come.

Leave a Reply