During the Mesozoic era, a fascinating group of marine reptiles known as plesiosaurs dominated the oceans. These creatures, characterized by their serpentine necks and four flippers, represented a diverse range of adaptations that allowed them to thrive in an aquatic environment filled with competition. One intriguing aspect of their evolution is the physical features that hint at their lifestyle and hunting strategies. Recent research has opened up new avenues for understanding the mechanics of their bodies, particularly the structure of their flippers and their unique skin adaptations.

Revolutionary Fossil Discoveries

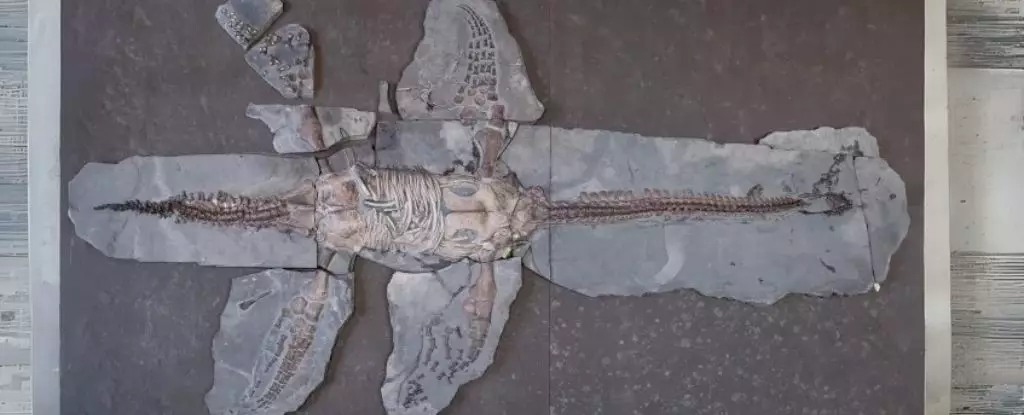

A groundbreaking study led by researchers at Lund University has unveiled remarkable details about plesiosaur anatomy through the analysis of a well-preserved fossil. Dating back approximately 183 million years to the Jurassic period, this fossil belonged to a 4.5-meter-long plesiosaur designated as MH 7. Notably, this specimen was excavated from Holzmaden, Germany, during the World War II era and has since provided invaluable insights into its morphological characteristics. The use of advanced techniques such as microscopy and spectroscopy allowed the research team to delve into the intricacies of the plesiosaur’s soft tissues, which have been scarcely documented in the fossil record.

Among the most striking revelations from the study is the discovery of flipper scales that resemble those of modern sea turtles. Unlike the smooth texture found on the plesiosaur’s tail, the analysis of the flipper skin revealed small triangular structures that suggested an evolutionary connection to aquatic reptiles. The team theorizes that these distinct anatomical features may have evolved under similar hydrodynamic pressures or environmental constraints, serving functionalities like enhanced swimming efficiency or aiding in locomotion across the seafloor.

Researchers propose that the scales on the trailing edges of the flippers provided vital traction and protective measures while foraging on the seafloor—a behavior consistent with palaeoecological findings that indicate plesiosaurs may have engaged in benthic grazing. This behavior not only illustrates their adaptability but also indicates a complex diet consisting of various sea creatures that thrived in their environment.

The rarity of soft tissues preserved from prehistoric creatures poses a significant challenge for paleontologists. With only a handful of plesiosaur soft-tissue samples reported worldwide, the evidence found in MH 7 stands as a critical piece in reconstructing the appearance and behavior of these marine reptiles. Interestingly, researchers also discovered pigment cells near the tail, which could provide insights into coloration and possibly thermoregulation, suggesting that plesiosaurs retained some warm-blooded characteristics.

In comparing MH 7 to contemporary reptiles, researchers noted that while the plesiosaur maintained scaly features, other marine reptiles of their time, such as ichthyosaurs, had adapted by losing their scales altogether—an evolution seen as a way to minimize drag while swimming. This divergence in adaptation reflects the ecological niches that these reptiles occupied and their respective survival strategies.

The research conducted by Marx et al. highlights not only the incredible adaptability of plesiosaurs but also their evolutionary significance as one of the most successful marine predators of their time. Their specialized features, ranging from unique skin adaptations to hunting strategies, showcase the wonders of evolutionary biology. As further studies build on this foundation, the enduring legacy of plesiosaurs continues to captivate the scientific community, offering a deeper understanding of life in ancient oceans and the adaptive mechanisms that have shaped marine reptiles through time. The findings not only furnish paleontologists with knowledge about past life forms but also encourage an appreciation for the diversity and complexity of evolutionary processes that occur even amidst changing environmental conditions.

Leave a Reply